A STORY of survival and a quest for acceptance, the life of Tea Gardens’ Lee Clayton has been brought to the stage in a new play depicting the lives of members of Australia’s burgeoning LGBTQI rights movement.

Lee joined the Campaign Against Moral Persecution (CAMP) in the early 1970s, a group formed in Balmain in 1971 dedicated to improving public understanding of homosexuality, easing the pathway to ‘coming out’ and reducing the isolation experienced by members of the LGBTQI community.

Advertise with News of The Area today.

Advertise with News of The Area today.It’s worth it for your business.

Message us.

Phone us – (02) 4981 8882.

Email us – media@newsofthearea.com.au

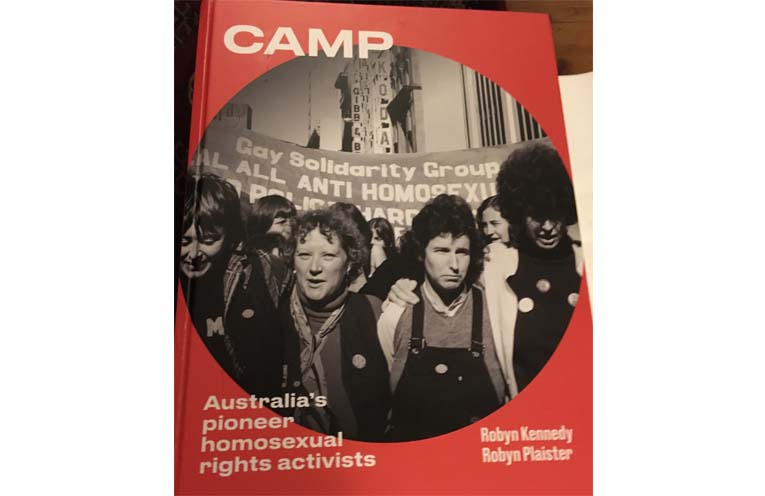

In September 2022, veteran CAMP members Robyn Kennedy and Robyn Plaister released a book, entitled ‘CAMP: Australia’s pioneer homosexual rights activists’, which featured Lee’s story.

With the book as inspiration, playright Elias Jamieson Brown and director Kate Gaul then brought CAMP to the stage, which ran in late February and early March at Sydney’s Seymour Centre.

Lee’s journey to involvement with the CAMP movement was not a simple one.

In her early late teens and early twenties, grappling with her sexuality, Lee described herself as “a very innocent young girl”.

“In terms of sexuality, I didn’t even know what I was, I had no idea,” Lee said.

“I was a virgin and I was very cotton wooled at home.”

At 21, after suffering a nervous breakdown while completing her nursing training, Lee was admitted to Chelmsford Private Hospital, a psychiatric institution in Pennant Hills.

“I was nursing at the time, and I hadn’t been very well.

“I was put in for what I am sure was PTSD, but there was no such thing in those days,” Lee said.

Her mother, who had been growing concerned with Lee showing interest in women, discussed Lee’s sexuality with hospital staff.

“I liked my teacher, and my mother thought that wasn’t okay,” Lee said.

“When I went into the hospital my mother said ‘she is really fond of girls and we don’t want that’.

“The sister said ‘we can sort that out’.

“They tried to sort me out but they didn’t quite manage,” Lee said with a wry laugh.

“They did a lot of awful things to me though.

“It was horrendous really.”

At the time, led by Dr Harry Bailey, Chelmsford Private Hospital was treating patients with Deep Sleep Therapy (DST), a discredited practice during which drugs are used to keep patients unconscious for up to several weeks at a time.

From the early 1960s to late 70s, DST led to the death of 25 patients in Chelmsford.

The hospital’s use of the practice, and other experimental treatment methods, was the centre of a Royal Commission from 1988 to 1990.

DST was prescribed for various conditions including schizophrenia, depression, obesity, premenstrual stress syndrome and addiction.

The hospital practised DST in combination with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), while brain surgeries such as the Cingulo-tractotomy were used, in Dr Bailey’s words, to treat “sexual immaturity”.

Lee has vivid and painful memories of her time in treatment at Chelmsford.

“There were people there who had ‘sexual problems’ and things like depression.

“I was in deep sleep therapy for a long time.

“I had anoxia three times, which is a lack of oxygen to the blood.”

In particular, Lee recalls the use of electroconvulsive therapy without anaesthetic.

“While they were doing the therapy they would also do the ECT.

““They used to do it bilaterally then, on both sides at the same time on your head.

“It would give you the biggest shock and spasms in my back.

“I can remember fighting it.

“We were shackled at our ankles and wrists and were in a wet bed, I can’t remember how long for, without the sheets being changed after we wet the bed.

“It was awful really.

“Years of headaches, slipped discs and pain, a back brace and urinary tract Infections followed this, and incontinence.”

To this day Lee is shocked that the hospital was allowed to practise these types of therapies at the time.

“Deep sleep therapy was really illegal.

“It had been outlawed in England and this doctor had come over to practise it in Australia.

“It was putting patients to sleep in very deep comas.

“Plenty of people died at Chelmsford through deep sleep comas.

“They also used to do awful things to the men and the boys.

“They would shock their penises and do horrible things to them.”

For Lee, the memory of Dr Harry Bailey, who committed suicide in 1985 while under investigation for his practices, is also an enduring one.

“He used to wear a monocle and Hawaiian shirts all the time.

“He was a flamboyant guy.

“People followed him, people believed him, otherwise this wouldn’t have happened.

“Doctors, nurses, even patients, believed this man.”

Eventually, after hearing that hospital staff had scheduled her for brain surgery, Lee was able to make her escape after a door was fortuitously left unlocked by hospital staff.

“I was buying some cigarettes one night from the machine.

“I overheard them saying they were going to send me to St George, which was where they would do the Cingulo-tractotomy – psychosurgery on my brain.

“I stopped taking my pills, and hid them in my cigarette box and put them in pot plants, but still acted like I was drugged up.

“One night it was about 2:00am and I found the door open and I got out and quietly closed the door and walked down the hill, though I couldn’t walk very well.”

Lee was able to make it to a nearby phone box and called a doctor she trusted, who arranged her to transfer to Ryde hospital.

“I will always love that man,” she said.

“He had worked at Chelmsford before and after a while realised that the treatments weren’t okay and he left.

“He knew it wasn’t doing what it was supposed to be doing, helping people.”

To this day, Lee has no idea how long she spent at the hospital.

“I don’t know how long I was in Chelmsford for.

“They sometimes keep you in deep sleep for a month or two months.”

A short time after her escape from hospital, Lee told her GP about the horrors she experienced at Chelmsford.

“She called me a liar,” Lee said.

“She said ‘that’s rubbish, nothing like that happened’.

“I didn’t say another word to anyone for twenty years.”

It was several years after her escape that Lee made initial contact with the CAMP community.

The group ran a coffee shop and meeting space in Glebe, produced a monthly newspaper called CAMP Inc, and ran regular dances and events for the LBTQI community.

“It was a place where you could be yourself, it was a safe way to be.

“It was in a little doorway on Glebe Point Road in Sydney.

“It was such a great place to be.

“I felt finally that I fitted In somewhere, meeting people who felt the same way I did.

“This was a place where we could meet, have a cup of coffee and just be ourselves.

“That’s how I originally got involved.”

Lee later volunteered her time at CAMP, greeting new members and welcoming them to the community.

“CAMP was about fighting for our rights, but I never got involved in politics or activism.

“I used to meet and greet people at the coffee shop two or three nights a week.

“When people were brand new, they were really nervous, it might have been their first time in a place like this.”

On weekends, CAMP members ran a hotline for LGTBQI people needing support.

“Phone a Friend was a counselling service operated by men and women 24 hours a day every weekend.

“These people were nurses and teachers etc, and they really helped so many people.”

With CAMP members’ stories brought to life on stage in recent weeks, Lee made the journey to Sydney to witness the production, which she described as “quite extraordinary”.

“The music, the sound and lights were all amazing.

“My story is woven through the whole thing.

“There were two actors playing me.

“Lou McInnes played me young and Sandie Eldridge played me older.

“When one came on, my daughter said ‘there’s you mum, they have got you to a tee’.

“The cast all came out later and gave me the biggest hug and thanked me for telling my story.”

Lee said the opportunity to tell her story, and watch it unfold on stage, was a cathartic experience.

“Watching it made me feel lighter.

“I didn’t realise I was hanging on to all this stuff.”

For twenty years following her experience, Lee remained silent, until by chance she saw a Chelmsford survivor being interviewed on 60 Minutes by Tony Ward.

“I started to shake.

“I couldn’t believe that someone was talking about this, and that somebody was believing them.

“At the end there was a number to call for people who had had the same experience.”

Lee made the call, and worked with a solicitor through the compensation process, eventually receiving $170,000.

Decades later, Lee has accepted her past and forgiven those responsible.

“I did that quite early on,” she said.

“I had to forgive them, or I would not have been able to go on with my life.

“If you hang on to this rage and hate and feelings of terror, you just make yourself sick.

“It doesn’t affect anyone but yourself.”

Speaking to News Of The Area in the recent aftermath of Australia’s Pride celebrations, Lee is pleased at the strides the nation has made towards acceptance.

“People should be treated how you wish to be treated.

“Whatever colour you are, if you have a faith – whatever faith you are, whatever sex you are.

“That’s the way I have always thought since I was a kid.

“I have never seen it any different and I never will.”

In the lead up to the NSW state election, both major parties made commitments to ban ‘gay conversion’ practices, a move Lee “can’t believe” hasn’t yet been made in the state.

“I can’t believe that it is still legal.

“People who don’t understand things, they have such a fear.”

Lee remains committed to her faith, based on Love and kindness, and attends the local Uniting Church.

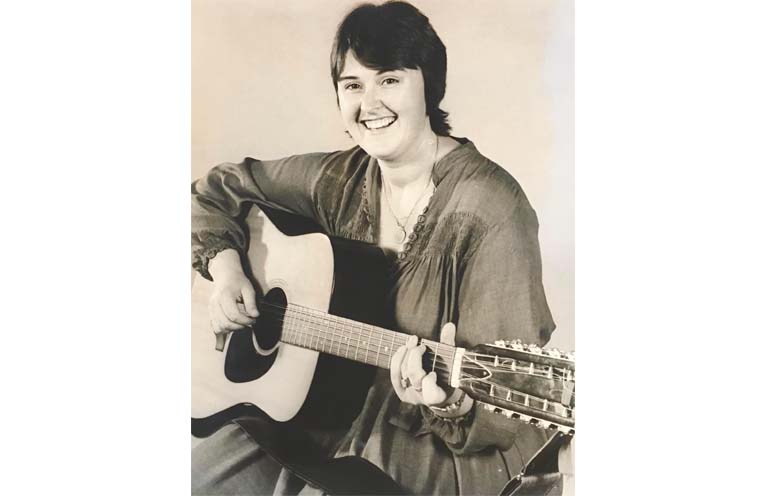

“I have faith in God and love not necessarily religious doctrine, and my faith and music and creativity has always been important to me.

“I also respect those who don’t have a faith or different faiths.

“We are all equal and we need differences to help this world be more interesting.

“Being inclusive about anything different doesn’t need to be difficult.

“We can all get on if we choose.”

Now residing in Tea Gardens, with family locally, Lee said she feels blessed by the life she has lived.

“I have a lovely life, lovely family, some good friends, I am involved in the community – what else do you want in life?

“I feel very grateful.”

By Doug CONNOR